A discussion article by PETER SOMERVILLE

Electricity generation is now largely privatised, and driven by market forces, across the world. It is not clear, though, whether such a system is up to delivering a transition from fossil fuels to renewable electricity fast enough to avoid catastrophic climate change.

Brett Christophers’ book, The Price is Wrong, reviewed here, provides a useful analysis of how the global system of electricity generation works. He explains how, without support in some form from government, renewable electricity cannot compete with fossil fuels in the longer term even if its price is lower.

Christophers argues that this is primarily because the rate of return on investment in fossil fuels is on average higher than in renewables, for a variety of reasons: insecurity of supply (absence of wind or sun), lack of grid connections and interconnections, and storage difficulties.

As global electricity demand continues to grow faster than renewable electricity supply (page 29), the gap between the two grows wider, and is filled predominantly by fossil fuels.

The key question, however, is: what is to be done? Here the picture is not so clear.

Christophers provides a number of brief references to alternative proposals for reform such as those by Dieter Helm, an energy researcher; the government’s Review of Electricity Market Arrangements (REMA); local pricing; market splitting; price-as-bid models, and so on. But he does not offer a clear explanation of why these proposals won’t solve the problem.

He argues that private ownership of electricity is inappropriate because electricity is not a “real” commodity, but this argument is not particularly convincing.

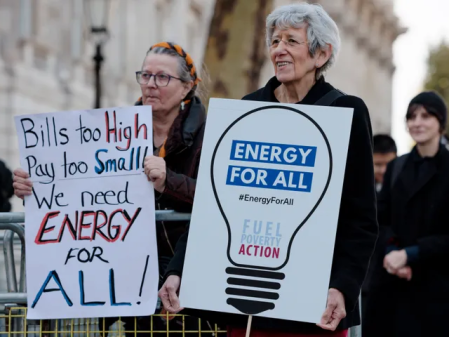

Public ownership of energy seems to be popular with the public[1] but that doesn’t necessarily mean that it is the best way forward.

Public ownership itself is a complicated business. There are at least three levels at which ownership of energy can occur. At the global level, energy production is dominated by private companies such as ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, Total, Chevron, and the rest – but also (and just as much) by state-owned companies such as Saudi Aramco, CNPC/PetroChina, National Iranian Oil and Petrobras.[2]

Taking public ownership of these companies’ assets in the UK alone would cost hundreds of billions of pounds, so would need exceptionally strong justification. But such justification is sadly lacking.

At the national level, the “big five” in the UK are said to be Centrica, EDF, E.ON, Ovo and ScottishPower.

□ Centrica is interesting because it is relatively “bundled” or vertically integrated, in that not only is it the largest energy retailer in UK (through its ownership of British Gas), but it is also involved in the wholesale market for electricity and gas, in gas production, investing in renewable electricity generation and in battery manufacture. So maybe vertical (re)integration is a possible way forward? Essentially, however, Centrica is bent on maximising its profits, not in decarbonising the electricity system.

The other four of the big five are relatively unbundled and not in a position to orchestrate any kind of energy transition.

□ EDF (Electricité de France) is already a publicly owned company, which also claims to be the largest generator of zero carbon electricity in the UK (though actually part of this is from nuclear power). Like Centrica, EDF is also heavily involved in energy retail and wholesale markets and battery manufacture.

□ E.ON is a German utility company, the second largest energy retailer in UK, heavily involved in district heating schemes, energy efficiency measures, provision of electric charging points, 100% renewable electricity for homes and SMEs, and solar panel installations.

□ Ovo and ScottishPower seem similar to E.ON but not as large. All five companies are very profitable, particularly Centrica.

The key question here is whether any of these companies will retain their profitability, as the share of their investments in renewable energy increases relative to their share in fossil fuels. The answer, however, is unknown.

If they do remain profitable, while still decarbonising sufficiently fast (which will mainly be due to diversification of their portfolios), then there would seem to be little point in nationalising them – though of course taxing their profits is perfectly reasonable.

On the other hand, if they get to the point where they are in financial difficulties, then that could well be the time to initiate something like New York State’s Build Public Renewals Act, as described in Christophers’ book (page 378).

What is not mentioned in this debate is the role of retail companies that already supply 100% renewable electricity, such as Octopus, Good Energy and Ecotricity in the UK.

In an unbundled market, of course, these companies are at risk of price volatility. However, they have survived the recent crisis (although many others have not), so would it really help if they were re-bundled in some way? Again, public ownership does not look like a clear way forward.

Also perhaps worth mentioning are the independent power generation companies that sell electricity directly to the grid, such as InterGen, who own four gas turbines, or Drax, who burn millions of trees every year. Do they have any future at all or should they be allowed to wither on the vine?

That leaves only the companies responsible for transmission and distribution of electricity on different geographical scales, such as national and international grids and connections across regions. In the UK the national grid is privately owned but, as a monopoly, it would seem more appropriate for it to be publicly owned.

The argument here is much the same as for water and rail: water at a local or regional scale, rail at a national scale. Dividends that are currently paid to shareholders could instead be reinvested in the grid.

The main problem with the current energy system, then, is that renewably sourced electricity is not being given sufficient priority relative to fossil-fuel-based electricity.

Perhaps the most obvious solution is for energy companies to be mandated to make the transition (the option stated on page 371 of Christophers’ book).

In stark terms, markets need to be shaped in order to avoid excessive global warming. This is not easy, of course, and public ownership must play its part, but this does not mean that anything like the whole system of electricity generation must be brought under state control – particularly when our political leaders are being driven by ideology and dogma and have precious little understanding of how the energy system works.

Pace the Labour Party, if it were really more profitable to invest in renewable energy, then the likes of Shell and BP would have transitioned long ago.

Christophers is probably right to emphasise that state intervention in the generation of renewable energy is necessary because such generation will never be consistently profitable enough for private sector actors (page 377), but the exact nature of this intervention remains a matter for debate.

Specifically, in taking a leading role on renewables, the state must show how public investment can “crowd in” investment from other actors such as private companies and community groups (pages 372-373).

This could involve at least partial re-bundling or vertical reintegration of the system as a whole. 13 June 2024.

□ Peter Somerville is Emeritus Professor of Social Policy at the University of Lincoln

□ This article continues the discussion on People & Nature about energy systems and energy policies. See also my review of the book by Brett Christophers here, articles on UK energy policy here and here, and a broader discussion of renewables here. SP.

[1] C. Shoben New poll Public strongly backing public ownership, Survation, 15 August 2022

[2] M. Grasso, From Big Oil to Big Green (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2022)